For $7 an hour, a teenaged Cesar L. Alvarez almost drowned laying cable underwater across Biscayne Bay in the ‘60s. The job, however, was far more lucrative than his previous stints as lifeguard, paperboy, burger-flipper and gas attendant. Regardless of his duties, the reward at the end of the week was always the same. “I worked hard for my milkshake at Dairy Queen,” he smiles.

For $7 an hour, a teenaged Cesar L. Alvarez almost drowned laying cable underwater across Biscayne Bay in the ‘60s. The job, however, was far more lucrative than his previous stints as lifeguard, paperboy, burger-flipper and gas attendant. Regardless of his duties, the reward at the end of the week was always the same. “I worked hard for my milkshake at Dairy Queen,” he smiles.

In those days, the rest of his earnings went straight to his family, who fled Cuba at the turn of the Revolution in search of new opportunities when Alvarez was just 13. “I’ll never forget the morning I was awakened at dawn and abruptly told we were going on vacation to the U.S.,” he says. “It seemed a little strange because we hadn’t been told anything about the trip and we were wearing every piece of jewelry we owned to complement the silverware stuffed in our pockets. I was taken aback because the last time we had visited the country, it had seemed fairly civilized…I did not see the need to bring our forks and spoons with us. Before I had any more time to think about it, we were boarding a ferry and were on our way. As Havana started fading into the horizon on that fateful day, I noticed that my parents were crying. I remember thinking to myself: ‘This is going to be a hell of a vacation!’”

Immediately upon arriving, they settled in North Miami and began a long assimilation process that would eventually yield a lucrative future for Alvarez and his siblings. “I was living in the moment for most of my youth,” he says. “But I always knew in the back of my mind that if I studied hard, and worked harder, I’d succeed.”

Immediately upon arriving, they settled in North Miami and began a long assimilation process that would eventually yield a lucrative future for Alvarez and his siblings. “I was living in the moment for most of my youth,” he says. “But I always knew in the back of my mind that if I studied hard, and worked harder, I’d succeed.”

Never one to turn down an opportunity, Alvarez borrowed $10,000 from the Cuban Refugee Collegiate Loan Program right after high school. In those days, tuition ran about $175 a quarter, which paid for classes, room and board, and books. “Back then I was able to get three degrees through the loan program,” he says of his B.S., M.B.A. and J.D. from the University of Florida. “During my undergraduate studies, I was particularly attracted to economics and finance, but the lure of law was too great, so I’ve always thought of myself as a business man first and a lawyer second.”

Although he was often side-tracked with dreams of investment banking and dabbling in other industries throughout his studies, once he graduated, Alvarez’s career path was peppered with perfect timing and lots of luck. The meteoric moment came when Mel Greenberg invited a fresh-faced Alvarez for an interview in the early ‘70s. “I didn’t even have a resume,” he recalls. “I know he wanted me because I was Cuban. Mel was one of the first lawyers in Miami to figure out that the Cubans would not be able to return, and were beginning to thrive in the Miami community. He wanted the firm to serve the growing Cuban community. ”

Alvarez says Greenberg greeted him with an interesting moniker when they first shook hands. “He called me Carlos, thinking I was my brother, who was a consensus All-American wide receiver at the University of Florida,” he says. “After correcting him once, and upon realizing he had no intention of calling me Cesar, I became Carlos during the rest of the interview process.”

Alvarez says Greenberg greeted him with an interesting moniker when they first shook hands. “He called me Carlos, thinking I was my brother, who was a consensus All-American wide receiver at the University of Florida,” he says. “After correcting him once, and upon realizing he had no intention of calling me Cesar, I became Carlos during the rest of the interview process.”

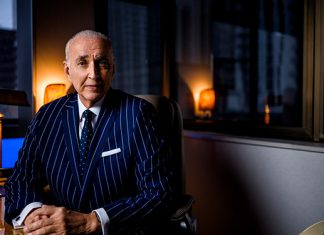

As a result of that humble introduction, Alvarez became the 13th lawyer to join the firm, and the first ethnic minority. Once he had his foot solidly planted in the door, Alvarez slowly worked his way up the ladder, often unintentionally. It wasn’t until he had the Bar under his belt that he was able to cut his teeth with real estate, securities, corporate and international law. But, as many rookie lawyers can attest, the transition wasn’t as easy as it looked. “I remember one time I went from Hialeah to Wall Street wearing my finest — a bright red shirt, shiny patent-leather shoes, a matching belt and a very flashy tie,” he laughs. “The snickers and grins from my NYC cohorts only motivated me more. Next time I visited, I had my pinstriped Wall Street suit on.”

Eventually, after 25 years of devotion to the firm that had given him a shot before he had a chance to prove his full potential, Alvarez was ready to lead a new generation into the future. And so it came that in 1997, Alvarez added three letters to his business card: CEO. “I don’t know why I was chosen to lead Greenberg Traurig during some of the most challenging times in history, but I can tell you it wasn’t because I was the best-looking!”

Eventually, after 25 years of devotion to the firm that had given him a shot before he had a chance to prove his full potential, Alvarez was ready to lead a new generation into the future. And so it came that in 1997, Alvarez added three letters to his business card: CEO. “I don’t know why I was chosen to lead Greenberg Traurig during some of the most challenging times in history, but I can tell you it wasn’t because I was the best-looking!”

Under his unconventional, open-door, team-oriented leadership, the firm grew from 325 lawyers in eight offices in 1997 to more than 1,750 attorneys and government professionals in more than 30 locations in the U.S. and abroad. “Throughout the years I have been blessed to be able to work with great partners who really are the reason for the firm’s success,” he says. Greenberg Traurig has been recognized as the fastest growing law firm in the U.S. and is one of the Top 10 largest law firms in the country, with more offices in the U.S. than any other major firm.

But it wasn’t all about success stories and praising headlines once Alvarez took the helm. He admits that after becoming CEO, things changed. “The interesting part about being a CEO is that the only real power you have is the ability to morally persuade and guide the lawyers and business staff to do what you feel is in their best interest and the interest of the firm. I have to make difficult decisions for the firm. My standard is always the same — to benefit the greater good and keep the business healthy. I go to sleep and wake up thinking about the birthday parties, weddings, anniversaries, holidays and special occasions that are contingent on the firm doing well. That’s not something I take lightly.”

But as much as he pays attention to the families of his employees, he candidly admits that it was a constant challenge to find the right balance between work and family as a result of the long hours he spent fulfilling his “outwork and outlast” motto.

But as much as he pays attention to the families of his employees, he candidly admits that it was a constant challenge to find the right balance between work and family as a result of the long hours he spent fulfilling his “outwork and outlast” motto.

It’s a message he echoes when he travels the country lecturing to aspiring law students. “Most people do things and go through the motions society expects of them without ever thinking about the end result they are trying to attain,” he says. “I ask them ‘What would you attempt to do in life if you knew you could not fail?’”

But success, he admits, can often provide a false sense of security. “The day I don’t feel like the underdog, is the day when I realize it’s time to put up my cleats,” he says. “Complacency is the biggest problem with success.” He adds that for too many people the road to success is dotted with a lot of comfortable parking spaces. “My road has been speckled with lots of ‘DO NOT PARK’ signs,” he says. “I have never allowed myself to park in one of those comfortable parking spaces.”

This philosophy has netted him the opportunity to meet presidents, senators, world leaders and top corporate CEOs. He has been a trustee, chairman and director for several major organizations in South Florida, helping countless people realize their dreams. He’s also received many honors for his work in and out of the boardroom including the “Spirit of Excellence Award” (2008) from the American Bar Association for his commitment to diversity in the legal profession, the “Lifetime Achievement Award” (2008) from Chambers and Partners , “Attorney of the Year” (2001) from the Hispanic National Bar Association, and “Humanitarian of the Year” (1997) from the Women’s International Zionist Organization. While being honored for the latter, he recalls a conversation he had with former UK Prime Minister and global activist Margaret Thatcher at the table they shared. “I remember when she was finished with her speech as the guest of honor, she leaned in to me and asked: ‘How do you think I did?’ — I responded, ‘I would have done it with more of a Cuban accent, but otherwise it was great!’ “

This philosophy has netted him the opportunity to meet presidents, senators, world leaders and top corporate CEOs. He has been a trustee, chairman and director for several major organizations in South Florida, helping countless people realize their dreams. He’s also received many honors for his work in and out of the boardroom including the “Spirit of Excellence Award” (2008) from the American Bar Association for his commitment to diversity in the legal profession, the “Lifetime Achievement Award” (2008) from Chambers and Partners , “Attorney of the Year” (2001) from the Hispanic National Bar Association, and “Humanitarian of the Year” (1997) from the Women’s International Zionist Organization. While being honored for the latter, he recalls a conversation he had with former UK Prime Minister and global activist Margaret Thatcher at the table they shared. “I remember when she was finished with her speech as the guest of honor, she leaned in to me and asked: ‘How do you think I did?’ — I responded, ‘I would have done it with more of a Cuban accent, but otherwise it was great!’ “

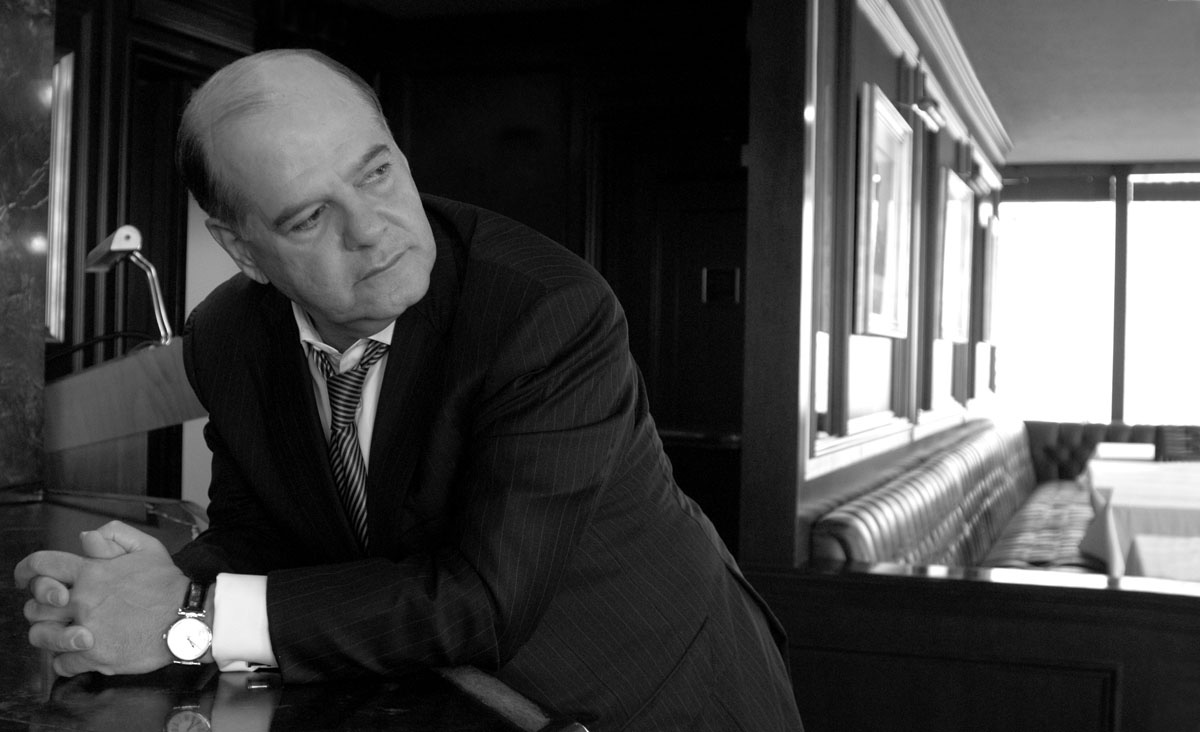

As the world looks forward to a new decade through optimistic eyes, the once-futuristic-looking 2010 is right around the corner and expectations are high. You can be sure Alvarez’s goals in his new role as Executive Chairman of Greenberg Traurig will be equally grand. “The business model for the legal industry needs to change. I want to make sure that our firm is a leader in this transition,” he proclaims. “It’s a goal I’ve been working on.”

As the world looks forward to a new decade through optimistic eyes, the once-futuristic-looking 2010 is right around the corner and expectations are high. You can be sure Alvarez’s goals in his new role as Executive Chairman of Greenberg Traurig will be equally grand. “The business model for the legal industry needs to change. I want to make sure that our firm is a leader in this transition,” he proclaims. “It’s a goal I’ve been working on.”

He cites many reasons for the need to refine the legal industry. At the top of his list is significantly lowering costs for legal services by creating more efficient working models through the education of lawyers on managerial and organizational practices.

Through it all, Alvarez remains authentically patriotic. “Our country has the greatest engine for economic success in the world: Freedom,” he says. “The spirit of entrepreneurship is in the DNA of every American. The U.S. is made up of self-selected entrepreneurs who have done everything possible in their power to get here. Americans adapt to change quickly. This resilience is something we can count on in an unsure world.”

Through it all, Alvarez remains authentically patriotic. “Our country has the greatest engine for economic success in the world: Freedom,” he says. “The spirit of entrepreneurship is in the DNA of every American. The U.S. is made up of self-selected entrepreneurs who have done everything possible in their power to get here. Americans adapt to change quickly. This resilience is something we can count on in an unsure world.”