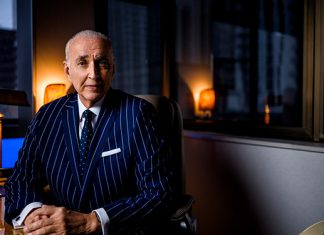

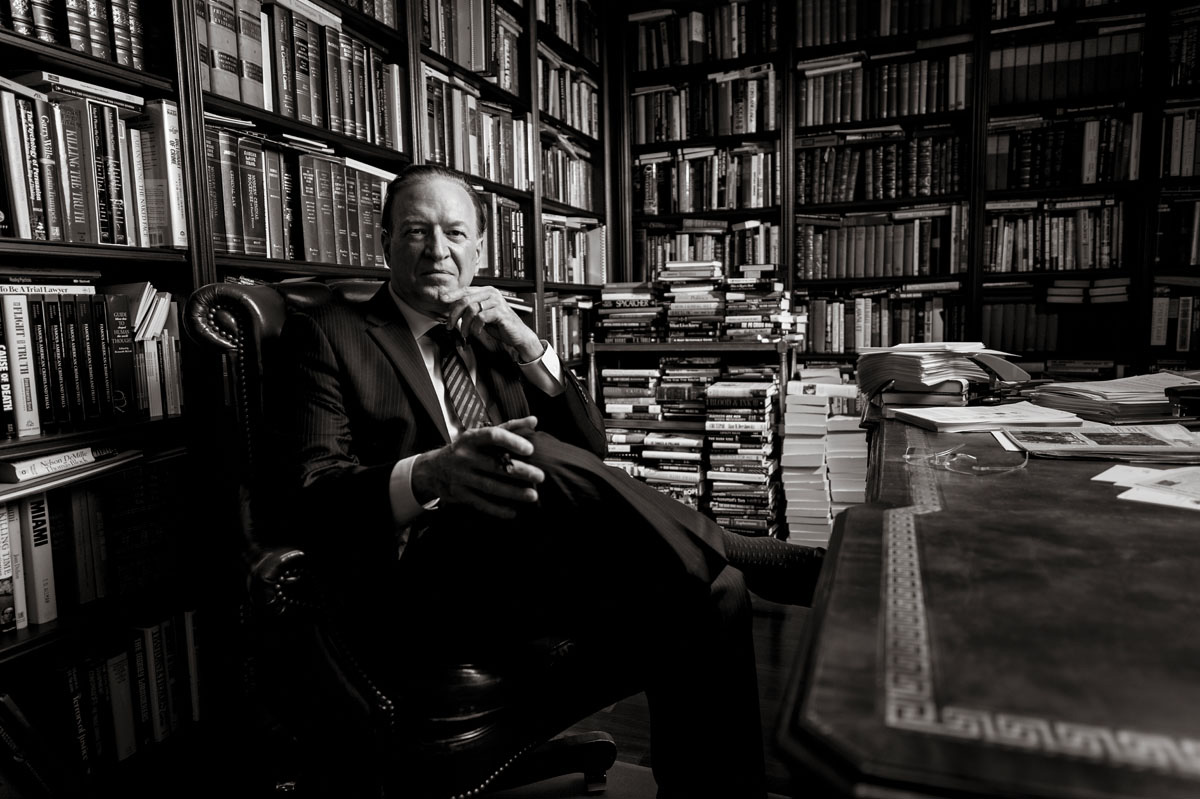

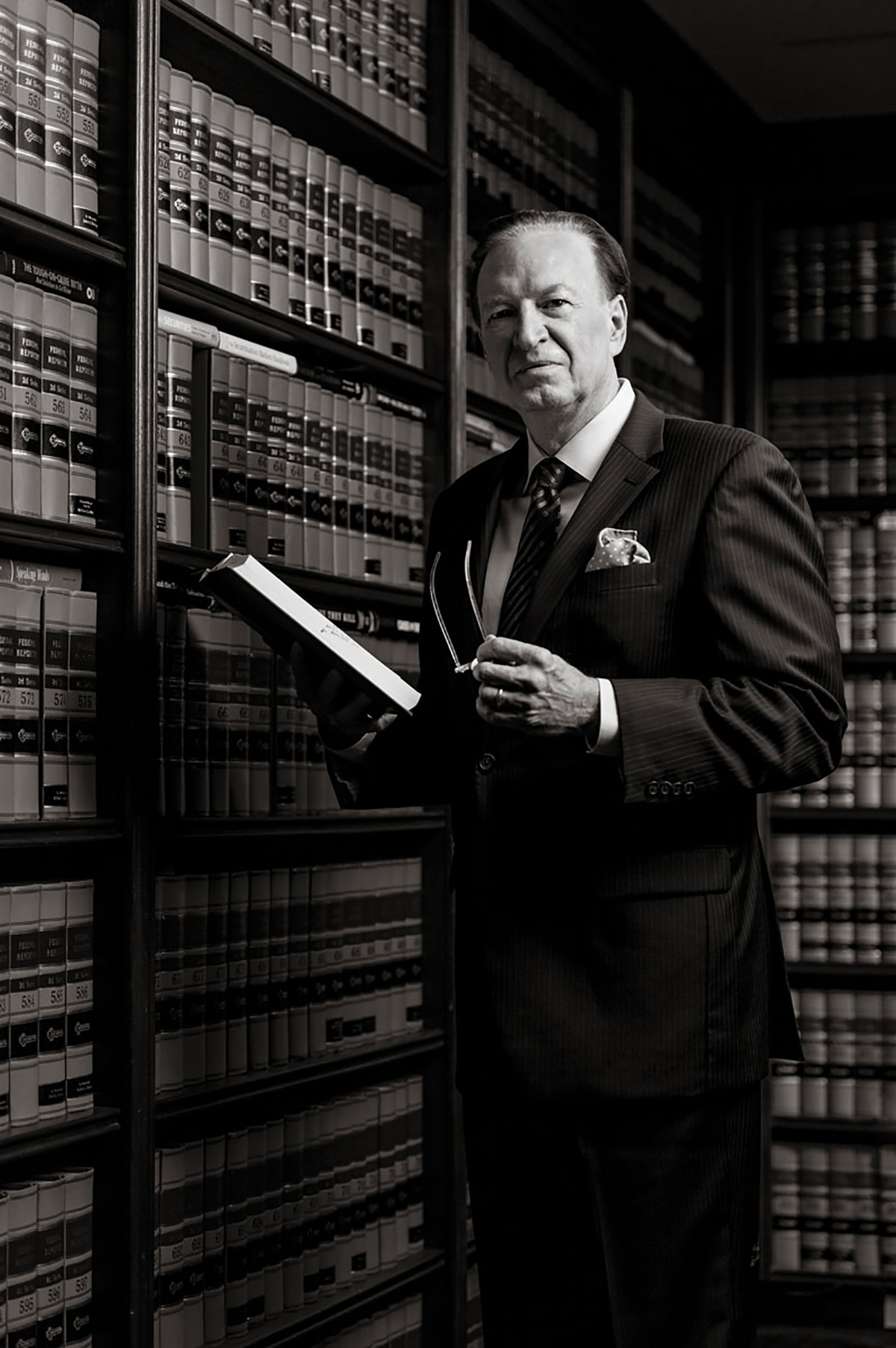

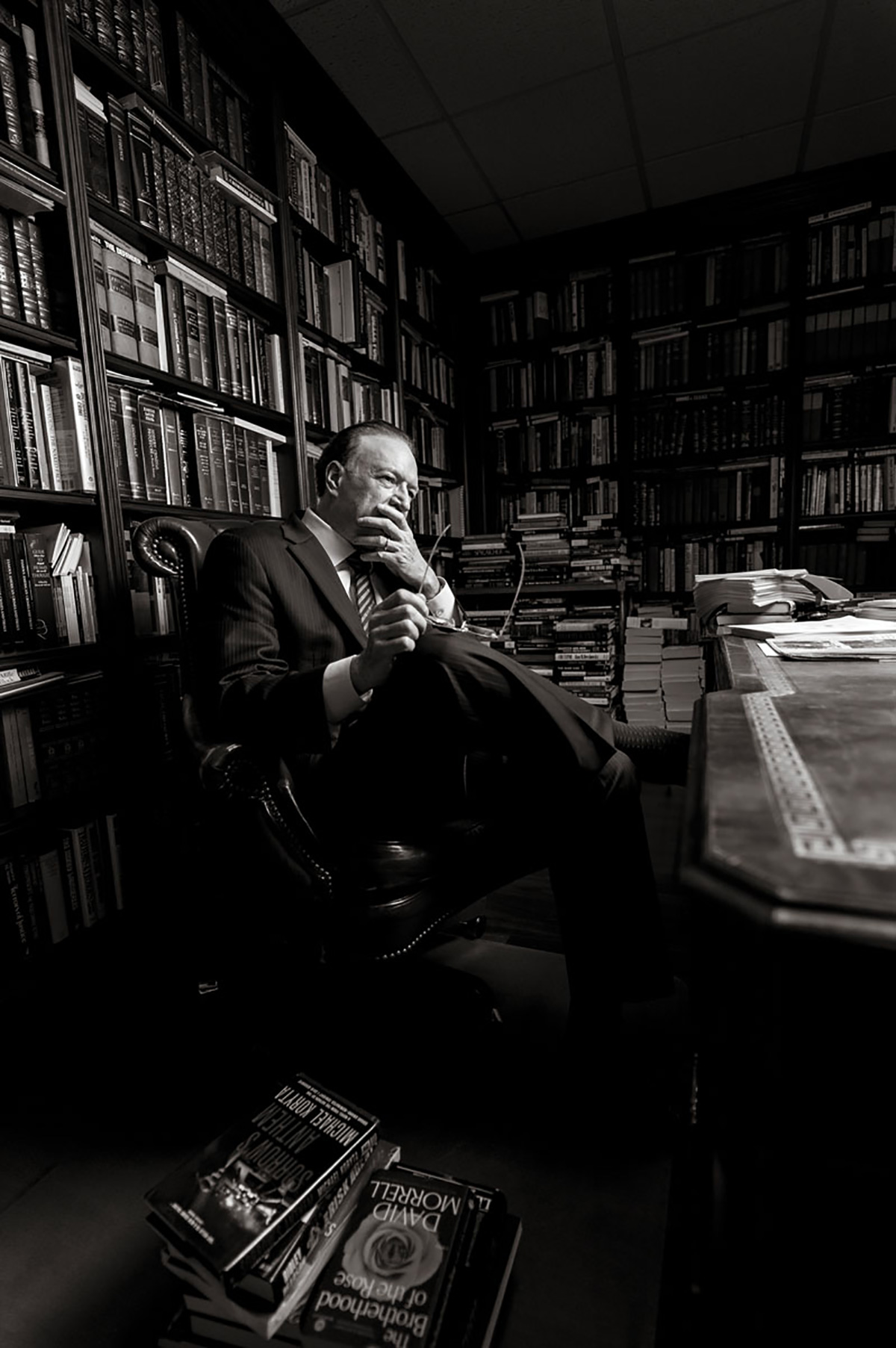

As much of a shark as he may be in the courtroom, Roy Black is surprisingly cool in person. His candid sense of humor and good-guy smile is laced with an uncanny wisdom that’s at once nurturing and sincere. This man really likes to make people feel at ease — and he genuinely likes to help folks who need it. It’s a temperament, an outlook, that he seems to have been born with and meticulously cultivated throughout his life and career.

As much of a shark as he may be in the courtroom, Roy Black is surprisingly cool in person. His candid sense of humor and good-guy smile is laced with an uncanny wisdom that’s at once nurturing and sincere. This man really likes to make people feel at ease — and he genuinely likes to help folks who need it. It’s a temperament, an outlook, that he seems to have been born with and meticulously cultivated throughout his life and career.

Born in Forrest Hills, NY and spending time in various states throughout his childhood, he never knew his biological dad, often joking that for all he knows, his father could have been an astronaut for NASA. When his mother, a hotel clerk, remarried, Black’s stepfather, a British WWII vet, had a pretty cool gig as a renowned auto racer, and eventually as an Executive VP for Jaguar North America.

When he was 15, Black’s parents decided to leave the U.S. and relocate to Jamaica after his stepfather took a job at an auto dealership in Kingston. It would be a shift that would forever change Black’s world view. “Before the move, I was a typical American kid in suburban middle America,” he says. “Everyone was white and everyone had dreams of becoming an executive in some company. I had little understanding of poverty or race. Most of us didn’t at that time.”

The first thing that struck him in his new country was how vastly different the schooling was. “The educational discipline I learned in Jamaica has done very well for me,” he says. “It was a much more structured form of learning, not as free-flowing as what I’d grown accustomed to in the U.S.”

The most important lesson he learned during his years in Jamaica came from an unlikely source: A math teacher who regularly gave him a hard time. “Every day, I’d go into his class dreading it. The guy was a real bully and did everything he could to humiliate me,” he says. “Whether it was because I was American or white, or a combination of both, for some reason he zeroed in on me from day one.” Black says the teacher would do things like make him get up in front of the entire class to work on extremely complex conversions and equations on the chalkboard, and he’d also regularly berate him in front of his classmates with snide remarks and mean-spirited comments. “Even though I was young, I knew there was no way I was going to let him break me, I wasn’t going to give him the satisfaction,” he says. “He was a prime example of how people with petty authority often try to intimidate others with the small amount of power they have.”

The most important lesson he learned during his years in Jamaica came from an unlikely source: A math teacher who regularly gave him a hard time. “Every day, I’d go into his class dreading it. The guy was a real bully and did everything he could to humiliate me,” he says. “Whether it was because I was American or white, or a combination of both, for some reason he zeroed in on me from day one.” Black says the teacher would do things like make him get up in front of the entire class to work on extremely complex conversions and equations on the chalkboard, and he’d also regularly berate him in front of his classmates with snide remarks and mean-spirited comments. “Even though I was young, I knew there was no way I was going to let him break me, I wasn’t going to give him the satisfaction,” he says. “He was a prime example of how people with petty authority often try to intimidate others with the small amount of power they have.”

After moving back to the U.S. during his senior year and completing his final year of high school in New York as valedictorian, Black had a couple of options at his disposal. On one hand, he had an offer for an academic scholarship to Columbia University; on the other, a swimming scholarship to University of Miami, a sport he’d taken part in throughout most of his education. Black chose the latter without hesitation. “Even though I’d never been to Miami, I was a kid, I liked the idea of going to a beach town and spending my free time having fun in the sun,” he says. “It felt like a good plan at the time, plus I was spending most of my time in the water anyway, so Miami was really a natural fit for me at that point in my life.”

Arriving in The Magic City with hopes of pursuing a degree in Oceanography while balancing his strict swimming schedule, Black realized during his 3rd year in college that his plans were taking him nowhere fast. “I was training up to 3 times a day while balancing coursework with studies and whatever social life I could muster, and eventually it just hit me that I had to reconsider what I was doing,” he says. As he was soul-searching for his next step, he remembered a teacher he admired back during his senior year in high school who dedicated his life to fight for the little people as a public defender. And then Black started to recall those feelings of helplessness he’d felt when that bully math teacher in Jamaica would berate him. “At that moment, I realized that practicing law was not only going to give me the knowledge to fight for my own rights, it was also going to give me the ability to help others,” he says.

Arriving in The Magic City with hopes of pursuing a degree in Oceanography while balancing his strict swimming schedule, Black realized during his 3rd year in college that his plans were taking him nowhere fast. “I was training up to 3 times a day while balancing coursework with studies and whatever social life I could muster, and eventually it just hit me that I had to reconsider what I was doing,” he says. As he was soul-searching for his next step, he remembered a teacher he admired back during his senior year in high school who dedicated his life to fight for the little people as a public defender. And then Black started to recall those feelings of helplessness he’d felt when that bully math teacher in Jamaica would berate him. “At that moment, I realized that practicing law was not only going to give me the knowledge to fight for my own rights, it was also going to give me the ability to help others,” he says.

So after graduating law school in 1970 and passing the bar with the highest score in the state that year, he began getting a series of appointments for jobs at various law firms. But it wasn’t until Election Day 1970 that his fate was sealed. While driving down Dixie Highway, he ran into Phil Hubbard, a former professor of his at University of Miami who was campaigning for public defender. “He took me out for coffee and offered me a job if he got elected,” he says. “We were both very interested in helping people.”

Hubbard won and kept his word and Black immediately went to work as a public defender. Under Hubbard’s leadership, he and his team made some pretty significant strides working primarily with poor minorities who were given very little dignity and respect in the system. Black explains the entire process was like a “conveyor belt system” whereas people would be arrested, charged, sentenced and often jailed without a fair trial. “The whole thing just felt wrong to me and I wasn’t having any of it,” he says. “We demanded trial by jury in every case — and the system almost came to a close because they couldn’t try all the cases. I was working 20 hours a day and handling up to 3 jury trials a week. It was extremely intense, but the best training grounds you could have. We had zero social life, but what we had was much more important: A cause.”

After cutting his teeth and developing an impressive portfolio of wins for more than half a decade, Black left and opened a law firm right on Biscayne Blvd. in 1976 before moving into his current digs at Miami Center in 1983. But, admittedly, it wasn’t an easy transition. “When I first left the public defender’s office in Jan. 1976, we were paid very modest salaries — I started at $8,500 per year — so I had no real savings to rely on,” he says. “I managed to cash in my state retirement fund and opened an office on a wing and a prayer, hoping clients would come. And fortunately they did. We only had a part-time secretary to start with so it was a low-budget operation…far different than the office we have today with a battalion of outstanding lawyers.”

After cutting his teeth and developing an impressive portfolio of wins for more than half a decade, Black left and opened a law firm right on Biscayne Blvd. in 1976 before moving into his current digs at Miami Center in 1983. But, admittedly, it wasn’t an easy transition. “When I first left the public defender’s office in Jan. 1976, we were paid very modest salaries — I started at $8,500 per year — so I had no real savings to rely on,” he says. “I managed to cash in my state retirement fund and opened an office on a wing and a prayer, hoping clients would come. And fortunately they did. We only had a part-time secretary to start with so it was a low-budget operation…far different than the office we have today with a battalion of outstanding lawyers.”

After branching out on his own, his first big case involved Luis Alvarez, a City of Miami cop who was accused of shooting and killing a young man in Overtown. “Miami at the time was a deeply divided city, a place of immigrant communities balkanized from each other,” he says. “Back then, nothing caused chaos more than a police shooting and the rampant misinformation about it. Immediately the street cop involved would be demonized and become public enemy number one. It was easier to blame one cop for our problems rather than the systemic prejudices and poverty in these communities. So the cop became the scapegoat. This was a cause I wanted to take on.”

Ultimately, the incident incited days of rioting and a fear that if Alvarez was acquitted, there’d be even more chaos in the city. “I remember getting death threats and having to take a private elevator with our own security to and from the courthouse for safety,” says Black, mentioning that after the acquittal, his firm’s profile raised substantially.

Ultimately, the incident incited days of rioting and a fear that if Alvarez was acquitted, there’d be even more chaos in the city. “I remember getting death threats and having to take a private elevator with our own security to and from the courthouse for safety,” says Black, mentioning that after the acquittal, his firm’s profile raised substantially.

With the Alvarez victory under his belt, Black’s firm started handling much more complicated cases including tax evasion and federal cases. His most famous case came with the William Kennedy Smith rape trial, which was aired nationally on Court TV. He landed the case after a firm representing Kennedy Smith backed out once additional allegations by other women started arising and the case became too toxic for other firms to defend. “It was the first major trial aired on Court TV and I was initially very skeptical, even fighting to block the cameras from the courtroom,” he says. “In retrospect, I think the whole thing was beneficial in that it allowed the public to make up their own minds once they saw all the evidence.”

Despite the national limelight and the impact of the Kennedy name on the case, the one thing that really phased Black was making sure he won the case. “It was a lot of pressure, but we rolled with the punches until we were confident we did everything in our power to yield a not guilty verdict,” he says. “I famously say that the only thing that really changed dramatically for me after that case is that I was able to get into Joe’s Stone Crab without waiting in line.”

Black’s next big client was William Lozano, a Hispanic police officer who was accused of 2 counts of manslaughter in the shooting deaths of 2 young black men. The case subsequently yielded 2 trials, 5-6 appeals and bouncing around to various courthouses throughout the state. The entire ordeal lasted nearly 5 years. “After being convicted in 1989, we were able to get the verdict reversed with a new judge in 1993,” he says. “Like the Alvarez case, what attracted me to this case was the underdog aspect of it,” he says. “Although street cops are the backbone of the public safety system, and put their lives on the line out on the tough, mean streets of the city, they’re also easy targets for anyone wanting to make a statement.”

Among other notable cases Black has successfully defended are: 3-time Indy 500 winner and Dancing With The Stars champ Helio Castroneves in a 6-week trial where he was charged with income tax evasion; Eller Media (now known as Clear Channel Outdoor) against manslaughter charges stemming from the bus-bench electrocution of a 12-year-old boy in Miami; and Albertson’s, Inc., when the State of Florida charged the Fortune 500 company with manslaughter in the death of a shoplifter. Other noteworthy clients have included Radio Talk Show Host & Political Commentator Rush Limbaugh, Sportscaster Marv Albert, Actor Kelsey Grammer, Artist Peter Max, Banker Fred De La Mata and WorldCom CFO Scott Sullivan, whose $11 billion fraud case yielded 1.2 billion+ emails to sift through. Black has also defended numerous other clients on charges ranging from murder to fraud and tax evasion. Black and his firm also handle select civil litigation, and have represented The Cordish Company, who was the developer of the Seminole Hard Rock Casino in a case brought against them by Donald Trump, as well as Rolls-Royce in several cases brought against them by the cruise lines.

Among other notable cases Black has successfully defended are: 3-time Indy 500 winner and Dancing With The Stars champ Helio Castroneves in a 6-week trial where he was charged with income tax evasion; Eller Media (now known as Clear Channel Outdoor) against manslaughter charges stemming from the bus-bench electrocution of a 12-year-old boy in Miami; and Albertson’s, Inc., when the State of Florida charged the Fortune 500 company with manslaughter in the death of a shoplifter. Other noteworthy clients have included Radio Talk Show Host & Political Commentator Rush Limbaugh, Sportscaster Marv Albert, Actor Kelsey Grammer, Artist Peter Max, Banker Fred De La Mata and WorldCom CFO Scott Sullivan, whose $11 billion fraud case yielded 1.2 billion+ emails to sift through. Black has also defended numerous other clients on charges ranging from murder to fraud and tax evasion. Black and his firm also handle select civil litigation, and have represented The Cordish Company, who was the developer of the Seminole Hard Rock Casino in a case brought against them by Donald Trump, as well as Rolls-Royce in several cases brought against them by the cruise lines.

“One of the problems of American life is that we’re obsessed with success, but then for some reason, we can’t wait to destroy folks who achieve it,” he says. “All you have to do is read the newspapers. People take joy when someone in the limelight is taken down…we all claim we don’t like it, but we love it. When a celebrity is charged with a crime, prosecutors and judges are extra harsh on them — but jurors love celebrities, even when they try to consciously remain partial. Famous people always have a better chance with a jury than with a judge.”

However, he says, the same is not true for those accused of financial crimes. “It’s frightening to be on trial today as a CEO, CFO, banker or developer,” he says. He also mentions that he advises his wealthy clients that there’s a big difference between business and the law. “Many times they discuss possible strategies with me that they believe will help their case and I always tell them when you are negotiating a business deal, both parties are equal, but in law, the playing field is not level and the stakes are much higher.”

When prompted whether he could share any historical dream cases he’d wished he could’ve taken on, Black admits there’s plenty including, among many others, Miranda v. Arizona, Giddeon v. Wainwright and Brown v. Board of Education. “I would’ve loved to take on big Supreme Court cases that changed the law and brought about significant social change,” he says. “These are cases that changed our society for the better.”

So what advice does Black have for lawyers? Well, he’s got plenty. “The education you get at school can make you a living, but self-education will make you a fortune,” he says. “For trial lawyers, I always tell them to drop those trial prep books and start reading business books. Knowing law is just a part of a great attorney, selling your side of the story is another.” Black also mentions that it’s essential to continually polish up your social skills and public speaking techniques. “When you’re at a party, go around and talk to people you don’t know and see how you can categorize each person. This skill will come in handy when you are selecting a jury pool.”

“In terms of public speaking,” he continues, “join debate clubs, take public speaking classes, find opportunities to speak in front of a large number of people. This goes back to developing a convincing argument. And this doesn’t just apply to lawyers — this goes for all professions. No matter what you do in life, you’re always selling — whether you’re a lawyer arguing in front of a jury or an entrepreneur applying for a loan. It’s all about how you conduct yourself in front of others and sell your side. It’s also important to thank anyone that constructively criticizes you and to credit those who inspire you without letting your ego get in the way — in the long run, it’s going to make you a much better version of yourself.”

“In terms of public speaking,” he continues, “join debate clubs, take public speaking classes, find opportunities to speak in front of a large number of people. This goes back to developing a convincing argument. And this doesn’t just apply to lawyers — this goes for all professions. No matter what you do in life, you’re always selling — whether you’re a lawyer arguing in front of a jury or an entrepreneur applying for a loan. It’s all about how you conduct yourself in front of others and sell your side. It’s also important to thank anyone that constructively criticizes you and to credit those who inspire you without letting your ego get in the way — in the long run, it’s going to make you a much better version of yourself.”

So what’s his favorite part of the job? “As lawyers, people come to us during the most difficult and frightening times of their lives — whether their money, house, family, freedom or life is on the line. It’s our job to have the skills to do the best we can for them,” he says. “Sometimes you’re up against the government, which has enormous powers that they don’t mind using. Poor you, you’re in this system they’ve created, with big impressive courtrooms and intimidating processes. But despite all those factors, we must never forget our core principle that everyone is innocent until proven guilty.”