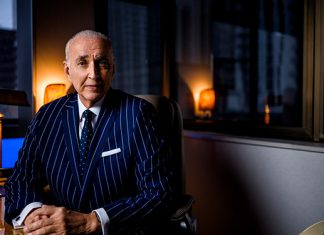

Frank Nero comes from a long lineage of builders and dreamers. The product of Italian immigrants who settled in North Plainville, New Jersey, his paternal grandfather was a mason; his mother’s father a gravedigger. Both his parents were factory workers: His mom a sweatshop laborer, and his father an employee at an electric motor manufacturing facility. Back in those days, during occasional summer jaunts to the Jersey Shore, Nero would dream of being a center fielder for the Yankees. He loved summers. In fact, he loved anything that kept him from school. “In high school, I was a troublemaker, and that’ keeping it PG,” he says. “My teachers, administrators and peers thought I was least likely to succeed — I was the school wise guy and I couldn’t wait to graduate and become a bricklayer or a barber.”

Frank Nero comes from a long lineage of builders and dreamers. The product of Italian immigrants who settled in North Plainville, New Jersey, his paternal grandfather was a mason; his mother’s father a gravedigger. Both his parents were factory workers: His mom a sweatshop laborer, and his father an employee at an electric motor manufacturing facility. Back in those days, during occasional summer jaunts to the Jersey Shore, Nero would dream of being a center fielder for the Yankees. He loved summers. In fact, he loved anything that kept him from school. “In high school, I was a troublemaker, and that’ keeping it PG,” he says. “My teachers, administrators and peers thought I was least likely to succeed — I was the school wise guy and I couldn’t wait to graduate and become a bricklayer or a barber.”

His then girlfriend, now his wife, wasn’t having any of that. She filled out a stack of college applications for him and sent them out before he had time to object. It seems love really can make you do some crazy things. “Besides my wife and a few teachers, there were very few people that believed in me,” he says. “Even my guidance counselor advised me that I wasn’t college material and I should aspire to be a mason like my grandfather.”

But something inside Nero caused him to swallow his destiny and give the idea of college a shot. Ironically, schools began courting him left and right, including an offer from Rutgers. “They must not have gotten the memo,” he laughs. “I couldn’t afford the big universities, so I had to make the best of my situation and went to state college. The most important thing was that I went somewhere before I changed my mind. I shudder to think about where I’d be had my life not taken the turn it did.”

And so it came that the disobedient little boy from Jersey polished up and arrived at Kean College, a sprawling campus just miles from the small town where he grew up. It was the perfect timing, too. Perhaps any decade other than the ‘60s may have produced a different outcome for Nero. A little bit of rebellion and lots of passion transformed him from troublemaker to “three-piece suit student body president.” “The Anti-War Movement, the emergence of the Counterculture, the Social Revolution and the Space Race — these were all things that fueled me,” he says. “I started to find myself, to develop this new persona amid the chaos. It was like somebody flipped a light switch in my head and all of a sudden doors opened that I never knew existed.”

For four years, he represented his college at the national level via various student organizations, dedicating his time to causes he believed in. He recalls one impacting moment in particular that occurred during the Civil Rights Movement, when he was hosting what was then called The Black Power Conference. During the gathering, he was handed a piece of paper that informed him Martin Luther King, Jr., had just been shot. “It was my responsibility to announce it to everyone in that room,” he says. “It was one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do.”

For four years, he represented his college at the national level via various student organizations, dedicating his time to causes he believed in. He recalls one impacting moment in particular that occurred during the Civil Rights Movement, when he was hosting what was then called The Black Power Conference. During the gathering, he was handed a piece of paper that informed him Martin Luther King, Jr., had just been shot. “It was my responsibility to announce it to everyone in that room,” he says. “It was one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do.”

Two months later, Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated, a particularly difficult tragedy for Nero to accept, as he’d been actively involved volunteering for the candidate and organizing students to rally their support for the candidate at college campuses throughout New Jersey. “Like many, I was moved by Kennedy’s urgency to unite America and leave behind the turmoil of the 1960s,” he says. “When word spread of what had happened, it was a traumatic experience that seemed as though the lights dimmed on the nation.”

Right after college, his goal was to make a difference and thank Karma for the opportunities he was given to change the trajectory of his life. And so it came that he served as an educator in an inner-city high school, training the next generation with all the lessons he’d learned along the way. Simultaneously, he took on community leadership roles. Putting his degrees and political experience to work, he went on to teach high school and college-level history, economics and political science. “I’m a firm believer, and living proof, that if kids are given an opportunity, they can succeed. Being easy on somebody doesn’t help them.”

Multi-tasking became a sixth sense for Nero, who juggled lesson plans with a whirlwind of elected and appointed positions at the state, county and municipal levels, culminating with one of the sweetest victories of his life: When he was elected Mayor of his hometown. But the journey toward earning that title was not easy. “Nobody wanted to run against the incumbent because the Mayor always won,” he says. But Nero had a different perspective. “Earlier, I’d approached the Mayor because I wanted to volunteer to help mentor kids and was turned away, so my dissatisfaction turned into motivation.” So it came that Nero, a 23-year-old teacher ran as the Democratic underdog against a Republican Mayor in a town where Republicans had been in power since the 1930s. “It was a close race, a third party Italian-American was entered to run in an attempt to siphon votes,” he says. “But I ran a very sophisticated grassroots campaign, knocking on every single door in the city twice.” With the support of his students, friends and family, they blanketed North Plainfield and got the young candidate enough votes to come out on top. “At the time, I was one of the youngest U.S. Mayors in the history of the U.S.,” he says.

After nearly a decade of inspiring youth and giving back to the community that had shaped him, it was time for Nero to affect the world on a grander scale, and once again challenge himself to evolve to the next level, this time with much bigger consequences. His new “campus” would be Capitol Hill. “When I told my parents I was planning to leave teaching for the Federal Government, they thought I was crazy,” he says. “They were shocked that I would leave such a secure job to take on more risky roles. I told them not to worry, that they’d done a good job with me.”

After nearly a decade of inspiring youth and giving back to the community that had shaped him, it was time for Nero to affect the world on a grander scale, and once again challenge himself to evolve to the next level, this time with much bigger consequences. His new “campus” would be Capitol Hill. “When I told my parents I was planning to leave teaching for the Federal Government, they thought I was crazy,” he says. “They were shocked that I would leave such a secure job to take on more risky roles. I told them not to worry, that they’d done a good job with me.”

If ever Nero were to tap into the skills he honed as a student leader it was now. “I was still influenced by the spirit of Bobby Kennedy’s policies and beliefs — I wanted to affect positive change,” he says. After all, he’d been preparing for it his entire life. As his career came to this crossroad, he was ready for the challenge. “I made the choice not to run for elected office again because of the strains on my family life,” he says. “In those times, most candidates relied on personal wealth to run their campaign, and I didn’t have that luxury.”

“I remember when the view outside my office window was all chickens and shotgun houses,” he says. “Today, Brickell is the one of the premier areas for all types of businesses and residential areas. Increasingly, people want to live, work and play here.”

He was first hired by Secretary of Labor Ray Marshall in 1977 to be a Regional Representative of the U.S. Department of Labor for Region II, encompassing New York, New Jersey, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. He was responsible for implementing policy in the region.

Then one day in 1980, his assistant received a call claiming it was from the President. “I laughed it off, thinking it was one of my buddies playing a practical joke,” he says. “I did not take the call.” The phone rang again and the voice on the other end said: “This IS the White House calling, the President needs to speak to Mr. Nero.” The call was in deed President Carter appointing him Chairman of the Federal Regional Council for Region II. “I still have my appointment letter framed comfortably on my office bookshelf,” he says. “I’m glad I took that call!”

Eventually, he realized he’d done just about all he could for his home state of New Jersey and the surrounding areas. He was ready to trade frigid winters for year-long tropical breezes. Nero was lured to Florida by way of a dual role he was recruited for in Jacksonville’s economic development sector, serving concurrently as Deputy Mayor for Economic Development and Executive Director for the Jacksonville Downtown Development Authority.

It seemed his achievements had echoed all the way down to The Sunshine State. Among many other accomplishments during his time in Northern Florida, he secured a new NFL franchise: The Jacksonville Jaguars. “It was a sweet victory,” he says. “The city went wild and it was all about celebrating the franchise win and getting Jacksonville on the map,” he says. “Up until that point, Jacksonville was a sleeper town.”

It seemed his achievements had echoed all the way down to The Sunshine State. Among many other accomplishments during his time in Northern Florida, he secured a new NFL franchise: The Jacksonville Jaguars. “It was a sweet victory,” he says. “The city went wild and it was all about celebrating the franchise win and getting Jacksonville on the map,” he says. “Up until that point, Jacksonville was a sleeper town.”

Then one day, a recruitment firm contacted him about an opportunity to head The Beacon Council in Miami. An extensive and rigorous interview processes followed, and ultimately The Beacon Council Board of Directors then-President Robert Beatty called and offered him the job. “I declined,” says Nero. “As soon as I got off the phone and saw my wife and kids packing, assuming I had taken the offer, I immediately called back, retracted and accepted. My family’s actions told me they were ready to move on.”

Since 1996, Nero has been President and CEO of The Beacon Council, Miami-Dade County’s official economic development partnership in charge of recruiting new businesses and helping local businesses expand. Through Nero’s leadership, the organization has been recognized as one of only 24 Accredited Economic Development Organizations by the International Economic Development Association. Additionally, Nero’s assisted close to 456 companies, helped create more than 32,000 direct jobs, retained over 10,000 jobs and attract more than $2.1 billion in new capital investment to the community. He’s also increased resources to market Miami-Dade County nationally and internationally to attract new companies. “When I came to Miami, there were less than 200 multinationals, now there are over 1,200,” he says. “As far as the percentage of international companies that The Beacon Council works with, there were approximately 20% when I came on board, now there are approximately 50%.” Most recently, Nero has championed a conversation on rethinking the “One Community One Goal” initiative that was created more than 12 years ago. “Since then, there have been extreme changes in the global and local economy, and thus we need to revisit it,” he says. “We’ve recently began evaluating a new targeted industry study, and in its initial stages, this is one call-to-action Miami-Dade can’t afford to ignore.”

As he looks out at the view of progress outside his office atop Brickell Bayview Center, he couldn’t be prouder of what Miami has evolved into. “I remember when the view outside my office window was all chickens and shotgun houses,” he says. “I was also the very first person standing outside of Perricone’s waiting to taste the new restaurant before they even had their sign up. Today, Brickell is one of the premier areas for all types of businesses and residential areas. Increasingly, people want to live, work and play here.”

And play he does, although not as often as he’d like. When he’s not handshaking atop skyscrapers or participating in a power lunch chat, you can catch him cruising around town in his cherry-red convertible Thunderbird 2002, complete with a shiny set of golf clubs in the trunk. “I always wanted one of the Early Birds,” he says. “When I was in high school, I made a model of a pink one for my wife, and I remember telling her that one day we’d have enough money to buy a real one. Nostalgia is a very powerful thing.”

And play he does, although not as often as he’d like. When he’s not handshaking atop skyscrapers or participating in a power lunch chat, you can catch him cruising around town in his cherry-red convertible Thunderbird 2002, complete with a shiny set of golf clubs in the trunk. “I always wanted one of the Early Birds,” he says. “When I was in high school, I made a model of a pink one for my wife, and I remember telling her that one day we’d have enough money to buy a real one. Nostalgia is a very powerful thing.”

As future generations of business leaders begin emerging on the horizon, Nero has some choice words of wisdom for them. “Don’t pigeonholed your options,” he says. “Back when I was younger, I couldn’t even imagine the job I have now existed. Try different things, don’t let anybody tell you what you can and can’t do. At the end of the day, you’re going to be doing whatever you choose for most of your life…you’d better like doing it.”

In the end, it seems Nero did take advise from his guidance counselor who told him he should pursue what he was born to do. “A lot of what I do is like a mason,” he says. “I was named after my grandfather, and I’m a builder just like he was, except I’m a builder of the next generation, a mason of the millennium.”